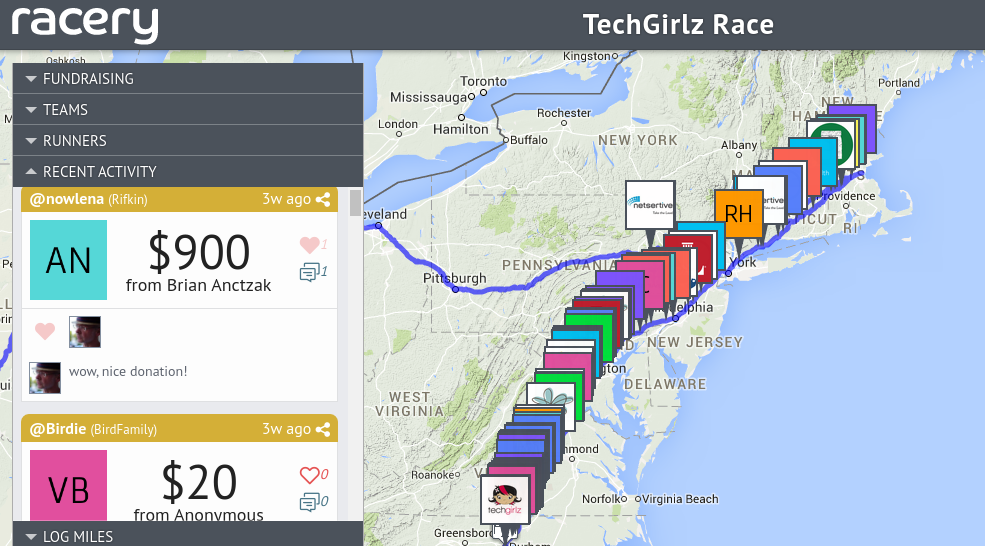

From many angles, our recent TechGirlz Virtual Race was a big success. More than 200 runners on 72 teams ran 19,653 miles in 40 days. In the process of the dashing and dishing, racers raised more than $7,000 for TechGirlz, a charity that helps middle school girls learn to write software.

Many contributions of time and money fueled the race’s success. TechGirlz volunteers like Clare Dupres, Deirdre Clarke, and Rachel Zarkin fanned the race’s spirit. The BANJ0 team — Adelaide Braddock, Nicole Erkis, Gabrielle Trotter, Joan Soskin of StratlS — were incredible fundraisers. And hats off to Brian Anctzak, CEO of Intuit Solutions which had five teams in the race, who stepped up with a $900 donation to honor their miles.

The race wasn’t perfect, though. In particular, the Racery team messed up by not setting out clear rules about the race’s finish. The final results left some racers feeling bruised and bemused. We were reminded that our understanding of virtual races — and our own role in them — is still a work-in-progress, even after more than two years of races.

What’s a virtual race?

Whether running 11-miles on Umstead Park trails or sipping a beer at Steel String in Carrboro or just sitting around in our Durham office, we’re often pondering — what exactly is a virtual race?

Technically, a virtual race enables people living anywhere to pit their day-to-day exercise miles against each other and watch everyone’s progress along a digital route. The result is a spirited competition. Lots of people tell us they enjoy their exercise more on our virtual races and that their daily mileage and/or frequency improve.

That’s the practical side. At a more theoretical level, a virtual race is a collective act of imagination, a set of assumptions and expectations shared in good faith by a bunch of people who want to strive and have fun together, and who trust each other… and us. In short, Racery is a game played by adults.

In hosting these races, we’ve stumbled on a paradox. Though a ‘virtual race’ sounds like it’s not real, by definition, we’ve learned these virtual races are effectively as real as anything else in our daily lives.

Every human interaction exists within a mostly unarticulated framework of ideas and beliefs. This framework is built atop a buried foundation, a many-layered sedimentation of motions and emotions. This foundation is so basic, so obvious, so common, that we rarely refer to it in our daily conversations.

Adult races are particularly easy to take for granted. They’re literally child’s play, barely modified from the dashes that kids instinctively launch across the playground, ending with a winner exulting “beat you!!” Few narratives close with a more universal and satisfying punch-line.

In ‘normal’ adult life, a race happens from point A to point B, from here to there, or, sometimes, from here to there and back again. Everyone starts on the same day, at the same time, in the same place. Each racer or team finishes when s/he/they get to The Finish Line.

In contrast to these concrete races, Racery’s virtual races are like holograms, untouchable and shimmering with arbitrary constructedness. Each racer picks where and when she runs each day. She moves in a vacuum with no spectators, fellow-racers or physical benchmarks. Without a tangible start or finish line, the race occurs in each racer’s imagination. The race’s reality only jells in an subjective space created in the moments it’s viewed on various screens, digital maps and electronic leaderboards.

Which leads to a question: what’s the role of Racery’s staff in maintaining or supervising this subjective reality? We’ve built the software and suggested a few rules that race sponsors can adopt for their races. For example, we suggest that race sponsors ask racers to not log miles accrued with step counters. This both encourages ‘intentional’ exercise and avoids the giant discrepancies that step counters sometimes foster.

Beyond these ideas, though, we’ve been pretty laissez faire, leaving the rules or guidelines or suggestions up to race sponsors or participants. We’ve viewed ourselves more as cheerleaders and water-station attendants than race directors.

The good news is that this openness and fuzziness sometimes creates useful new templates. Duke University School of Nursing (DUSON) decided that for their virtual race between students, staff and faculty, which has now been going on more than a year, an hour of hot yoga can be credited as 6 miles on the virtual route. Other race sponsors have now adopted that idea too. Some might argue that an hour of hot yoga isn’t actually worth 6 miles, but if enough people at DUSON agrees 6 miles is the right number, that works just fine for us.

As much as we’d like for Racery’s staff to remain neutral and invisible, stage hands rather than actors, our software does designate winners by generating leaderboards. After weeks of virtual jockeying, these public declarations make the lines crisper; the races seem more real and objective. And, as we discovered at the end of the TechGirlz Race, this crispness can shove Racery’s staff into taking a more active role in managing races. This was a new experience for us.

The Tech Challenge

Our relationship to the rules and spirit of these virtual challenges was spotlighted when the TechGirlz Race ended. The race was scheduled to last from March 21 to April 30, 2016, with teams of up to four racers amassing as many miles as possible in that period.

In this particular race, we requested that only running and walking miles should be submitted, with no step-counters allowed. Still, there was lots of variation in how people counted their miles. Based on anecdotes we heard from TechGirlz participants, some people religiously submitted only miles they’d run. Other people counted miles run, plus miles accumulated walking the dog, etc.

Our virtual races involve everyone from ultra marathoners to 1-mile-a-day walkers. All our races are fun and motivating, but some tap into more competitive spirit than others. Though this race had no entry fee or physical medal, the competition in the final days turned out to be as fierce as any we’ve seen in a “normal” contest. A couple of teams went the crazy bad-ass distance of 900+ miles total over the 40 days. (By comparison, Racery’s team accumulated 535.7 miles, and as someone who is happy to top 100 miles in a month, I’m awestruck by these teams tenacity.)

As I mentioned above, we had more than 200 people racing. In the end the gap between the top two teams on the leaderboard was only a minuscule 0.1%. In the race’s final day, the Swifties team of four logged a total of 61.2 miles. That feat put them atop of the team leaderboard that was public on Racery.com, and likewise, they were there when our software generated placards for individual’s placements the next day. (The Swifties were also tops in creatively quoting Taylor Swift lyrics as they posted miles.)

As of midnight 4/30 and through Monday morning, 5/2, the Swifties were the race’s clear winner, as one of its members noted in a tweet.

We did it! Swifties finish 1st with 990.6 miles and raised $90 for @TechGirlzorg in the #techgirlzrace pic.twitter.com/9ETE2sdYkS

— Mark Lavin (@DrOhYes) May 1, 2016

Monday morning, a Netsertive-3 team member asked if Racery could log his 11 miles, run but not submitted on Saturday. What to do? Here’s what factored into the decision to log those miles.

First, there’s our normal ‘can-do’ approach to racer questions — members of our team frequently fix, edit and backdate mileage for racers. We ask no questions, relying on the honor system that underlies all our mileage submissions. Our goal is to respect each racer’s reality: these races are not written in stone but pixels. On occasion, we’ve even extended the duration of races when participants have been surprised by how quickly they’ve traversed a particular distance.

Second, we noted that our regular e-mails to racers urge people to ‘submit mileage anytime,’ and without thinking about what these additional miles would do to the leaderboard or Swifties’ #1 position, we added the 11 miles.

And we quickly got called out on it. The Swifties were justly surprised and annoyed.

.@raceryapp Based on the results email and my screenshot it looks like ~11 miles were added after the cutoff ಠ_ಠ https://t.co/th4O5Rpzph

— Mark Lavin (@DrOhYes) May 2, 2016

After reading the tweet and realizing the ramifications of this 11-mile addition, we had a number of internal discussions, rereading the language in our interfaces and various automated e-mails we send to racers, and discussing our overall sense of the spirit of these races.

What is the “end” of a virtual race during a stated time period — is it miles run and submitted by the end time, or miles run before the end time?

There are lots of ways of slicing this cake, all of them arbitrary. Fitbit, for example, gives racers an extra 12 hours to log miles and also factors in time-zones.

On the one hand, we dug around and couldn’t even find any well articulated “rules” for this race. Doh! Worse, we didn’t find an affirmative statement of the race’s temporal finish-line, something as straight-forward as “only mileage submitted before midnight will be counted.” Doh #2.

We kept coming back to the words in the e-mail we sent every day to racers: “Did you know you can submit miles to this race at ANYtime?” (Emphasis in the original.) We hadn’t had the brains or foresight to use a word as temporally definitive as ‘deadline’ or ‘cutoff,’ which would have perfectly nailed things down. Doh #3.

On the one hand, words like ‘closing,’ used in several of our race e-mail templates, implied (as when people in some locales keep imbibing even after the barkeep shouts ‘closing time’) or demanded (as with a door shutting) no more mileage entries processed after a certain fixed time. And, on 5/01, racers trying to submit miles via the race interface got a message saying “race closed as of 4/30 23:59.” (Compounding our sloppiness, no time zone was mentioned. Should that have been 23:59 GMT… or further west or east, since this race had participants from as far away as Singapore?)

Stepping back from our fuzzy and contradictory language in the interfaces and e-mails, we thought about this race’s spirit. If you’d asked us before diving into all these nuances, we’d probably have said that that miles would be covered within a certain date range. (This was the first time we’d hit the problem of determining the exact meaning of ‘race’s end’ — our early races were all from point A to point B, where, more obviously the first person or team arriving at B is the winner.) Further unpacking the spirit of our virtual races: we, and everybody else who wants to participate in these virtual races, need to trust that racers log mileage in good faith.

Which lead us to another question: beyond building software and answering racers’ questions, what’s Racery’s role in all of this? Are our virtual races like a pro football field where calls are governed by refs in the rafters staring at TV screens? Or are they more like like Ultimate Frisbee, where there are no refs and so all players gather on the field to negotiate any disputed calls?

We decided that our races are more like Ultimate Frisbee than football — everyone trusts each other and (currently) no money is on the line. When there’s a disagreement, the spirit of the game is invoked. Should we hold a vote among racers? That seemed impractical, so we reached for another sports model, deciding our role in cases like this would be like that of a baseball umpire pre-2014 — the few times when situations are ambiguous and pride was on the line, the ‘reality’ is whatever the ump says the final call is.

Considering the above and having accepted Netsertive-3’s final 11 miles and emailed all racers with the resulting team leader board with Netsertive-3 at #1 on the afternoon of Monday, May 2nd, we decided to stick with that finish. We’ve added a footnote to the race’s About page addressing the multiple time-lapse outcomes.

To improve the Racery experience for future racers, we’re revising our internal processes and guidelines. For each race, a deadline for submissions affecting leader boards will be clearly specified and labelled as such. We now use the word “deadline” and say “no miles will be accepted after” in default communications to racers. And, from a technical side, the finish line will also be more clearly defined because all placards for placement — both team and individual — will be created at the same time based on the standings as of that moment. (We’re currently transitioning out of distributing team placards manually.) Any mileage submissions after the end of a race won’t impact leader boards, but can still affect an individual’s personal records and achievements. (I guess if we ever start giving system-wide awards for ‘most runs’ or ‘longest distance in a period,’ we’ll have to revisit this too.)

FInally, since the race results depend on the goodwill of all participants and are not scientifically determined, we’re changing the wording on the digital awards we give for individual and team placements. These previously read ‘certified by Racery’ but, as of last week, bear the words ‘powered by Racery.’ In retrospect, ‘certified by Racery’ implied more science and certitude than we can muster.

Looking forward, we better understand how much passion a virtual race can evoke. Though our routes are made of pixels, they’re measured by real blood, sweat and tears. And we better understand that our staff is the custodian of these virtual races, a role that’s more nuanced than being a proprietor or director or cheerleader or host. It’s a role we’ll have to continue to think about and improve at. (Which is partly why this blog post is preposterously long.)

Again, we deeply regret our contradictory language and frustrating the Swifties, who poured on the miles to put their team at #1. We’re thrilled to have more than 200 people celebrate the TechGirlz charity and help raise $7k. And we appreciate the opportunity we got to improve Racery.